Creating an Inclusive Course Environment

This post contains tips on how to create an inclusive course environment. Much of this perspective on pedagogy has been sourced from conversations with some of CS 161’s veteran TAs - Peyrin Kao, Vron Vance, Nicholas Ngai, Fuzail Shakir, and others - as well as from the professors who’ve taught CS 161 over the past few semesters: Nicholas Weaver, David Wagner, and Raluca Ada Popa.

This is a work-in-progress. If you have comments, shoot me an email at shomil@berkeley.edu or ping me via Slack.

Feedback

Ask for feedback, and ask for feedback often. I’m starting with, arguably, the most important tip - even if you ignore everything else in this post, please, please do this. Many of the tips I’ve noted here are based on thousands of data points collected through feedback that we’ve sourced directly from students.

In CS 161, we ask for feedback in two critical places: at the end of each homework assignment in a free-form text box, and immediately after an exam takes place. Asking for this free-form feedback allows us to interface directly with students & resolve concerns as they arise.

Here’s the question we use to ask for feedback, and an example feedback submission we received from one of our students:

We have a script that scrapes this feedback from Gradescope and dumps it into a Google Doc, which we then review at our weekly staff meetings.

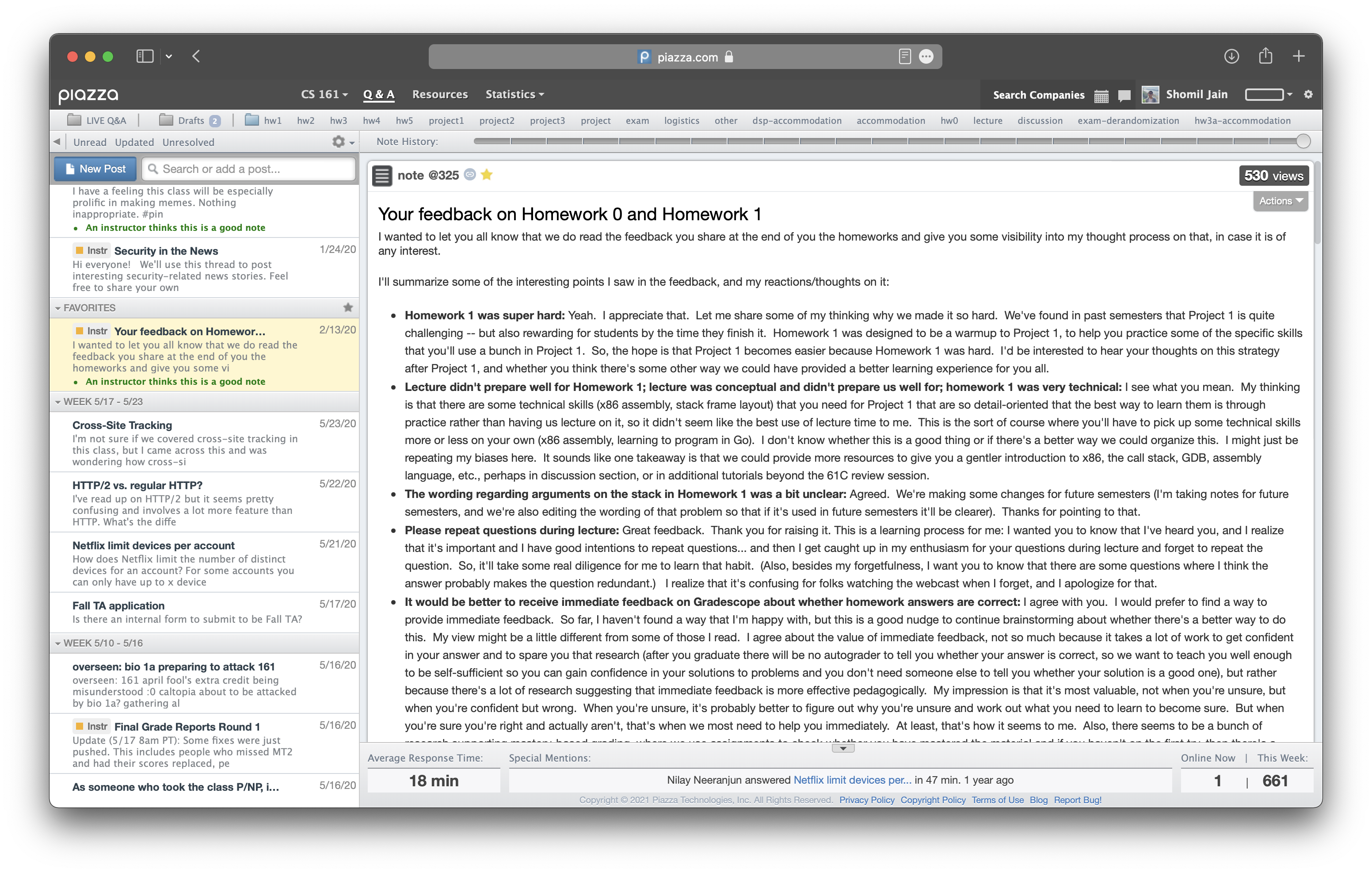

Occasionally, concerns raised through feedback may be significant enough to warrant a standalone “response” post. Here’s one that David Wagner posted in the Spring 2020 iteration of CS 161, back when I was a student:

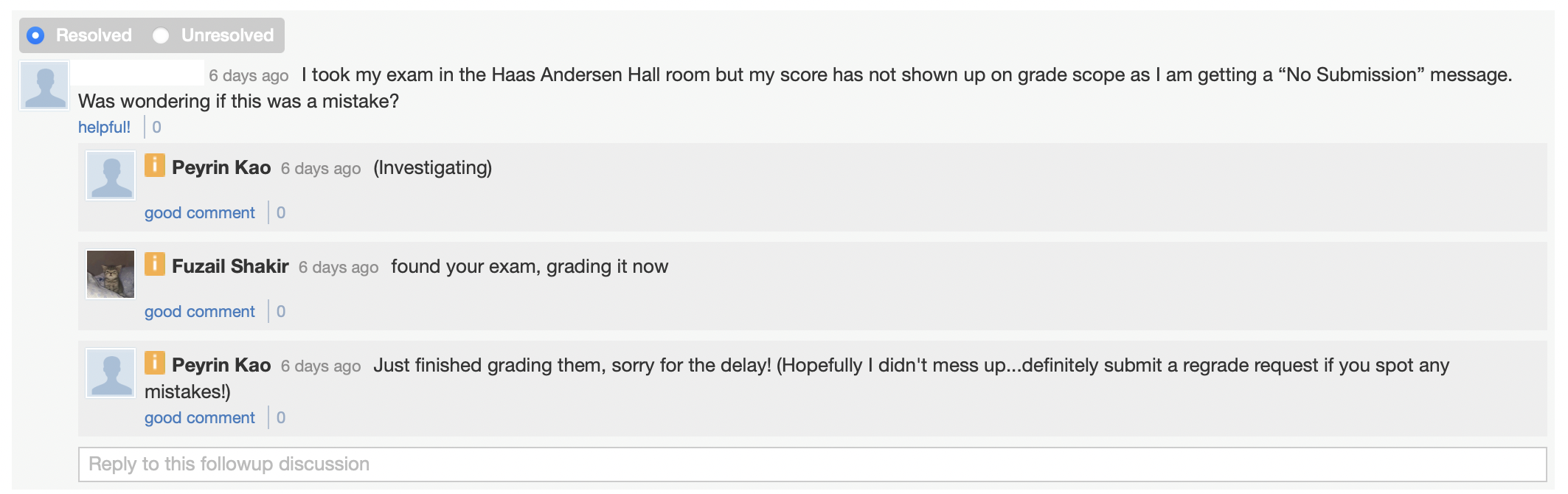

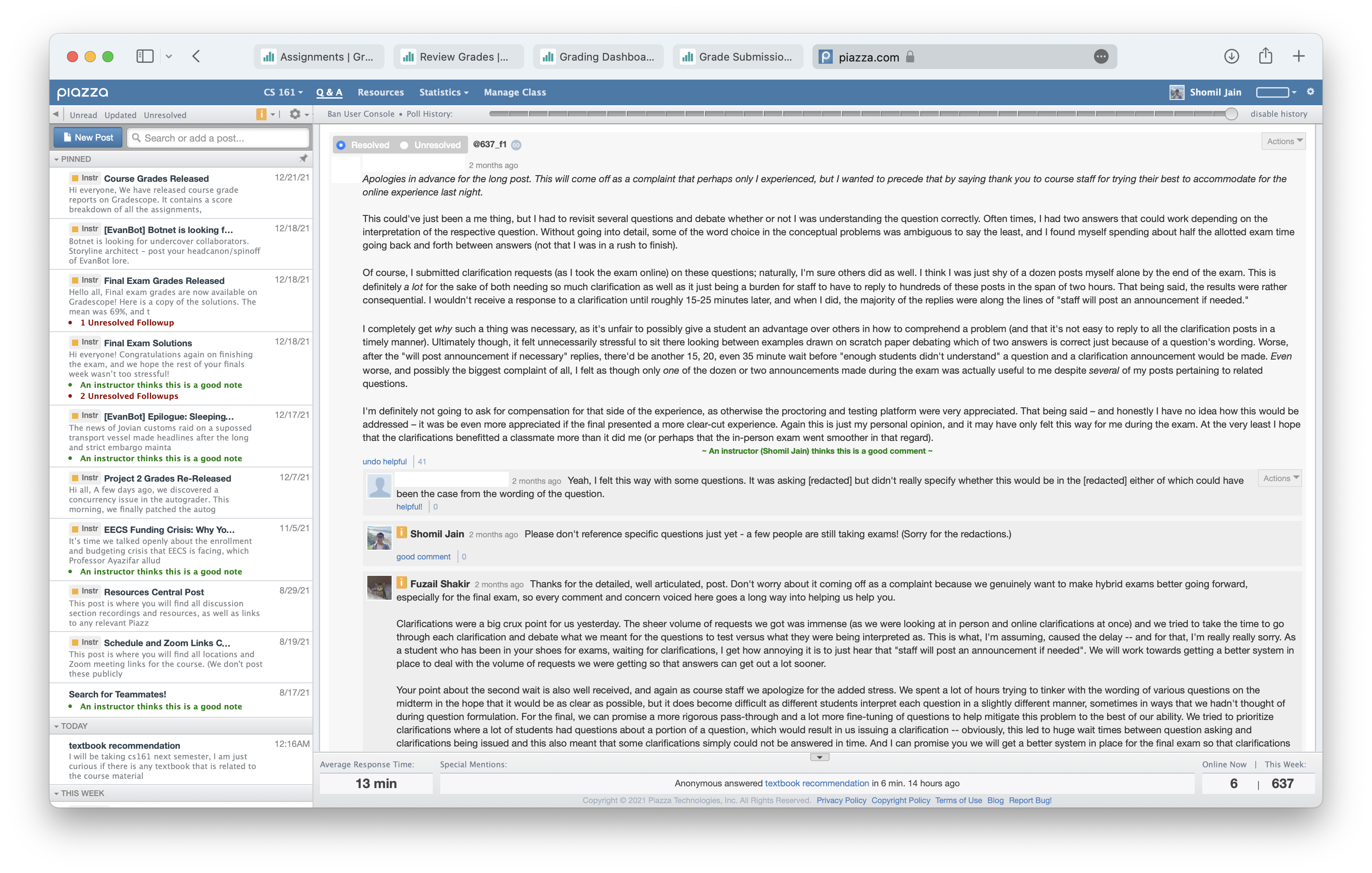

These feedback channels are also a critical component to making students feel heard & building a community in which people feel included, aren’t afraid to ask questions, and share their frustrations constructively (as opposed to destructively). Here’s an example of feedback (and response) from one of our “How did the midterm go?” posts earlier this semester.

Aside: for the particular issue above, we course-corrected for the final by dedicating more time/care towards exam pre-testing and having more TA’s in the clarifications room.

Content

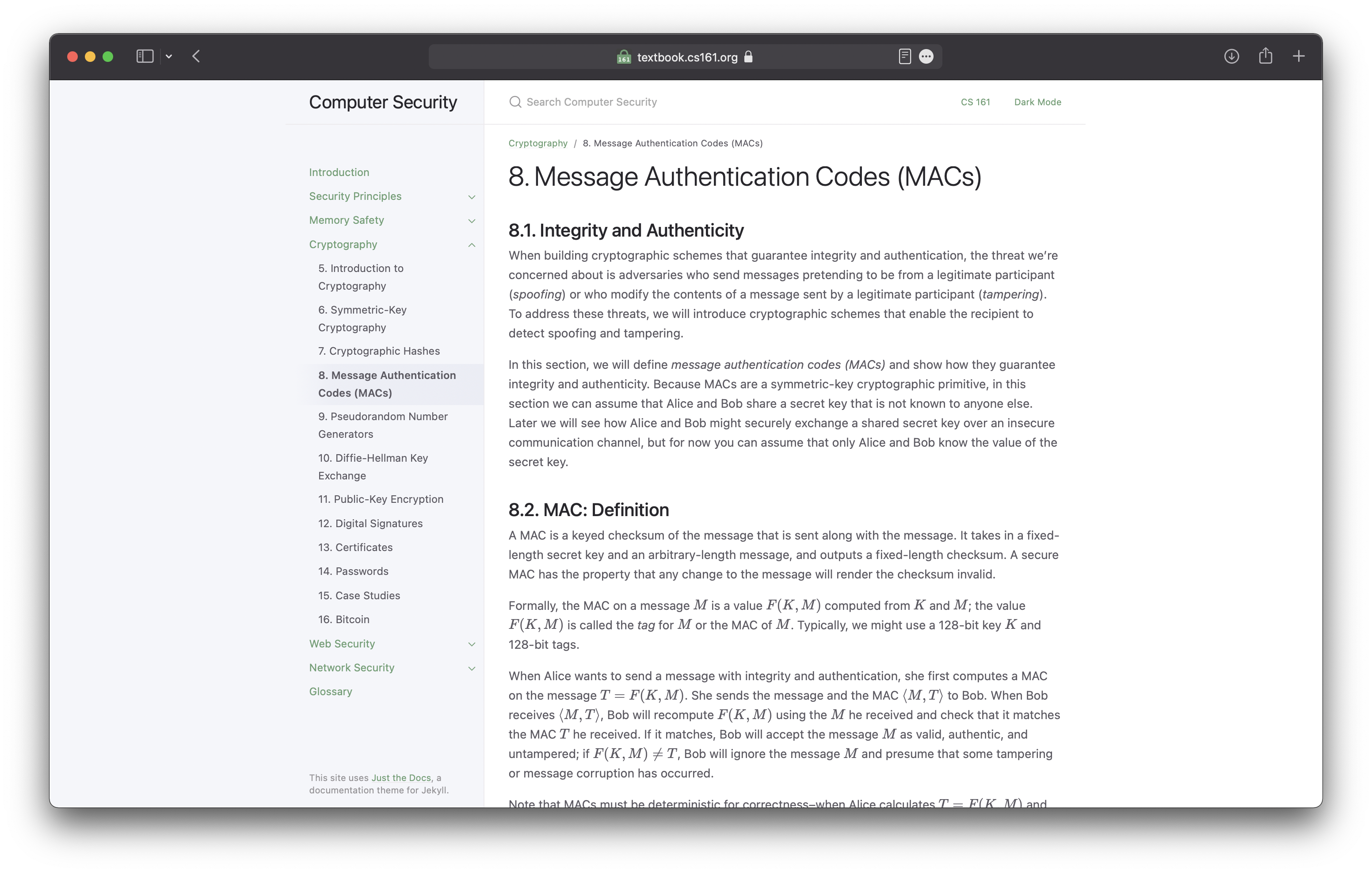

Deliver content through multiple forms, if possible. Over the past few semesters, we released a course textbook to supplement and enhance lecture. We did this to support students who better understand content through text (as opposed to verbal/graphical content delivered through lecture & lecture slides). This semester, I also put together a Networking 101 slide deck that covers the foundations of networking in more depth than our traditional lecture slides - this was also well received by students.

Not everyone learns the same way – so if you’re able to provide several different methods of digesting course content, then do so.

CS 170 does this really, really well (they offer lecture, reading, section/section walkthrough, mini-lecture/conceptual walkthroughs, and assignments/assignment walkthroughs).

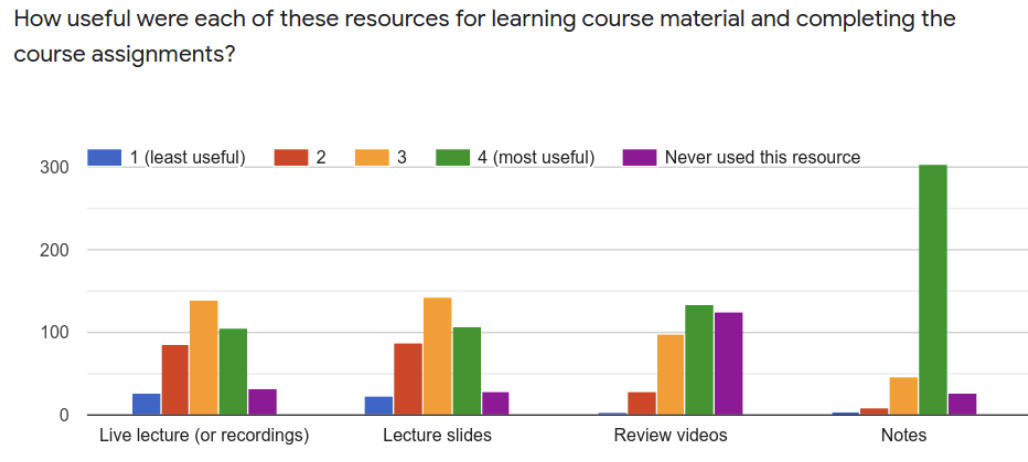

Also, collect data on what works for students - and put TA hours toward building out the things that work. We polled students on how helpful they found the textbook in SU21 and FA21 (while we were actively developing it), and we saw an increase of nearly 20% of students who rated the helpfulness of the textbook a 4/4.

People generally like video walkthroughs of things. Our video walkthrough for Project 1 (1300 views) and Project 2 (900 views) were among our most-viewed videos for the entire semester. We have a hunch that these were particularly helpful to students who were conceptually behind and/or felt lost – considering we had only 600 enrolled students, it seems many students referenced these videos several times.

Logistics

Be lenient with extensions. Life as a student (especially at UC Berkeley) is often fatiguing, chaotic, and incredibly stressful. As instructors, many of the things we do directly and indirectly affect our students’ mental health. If we’re given opportunities to reduce student stress (e.g. through a one or two-day extension, a few added slip days due to power outages, etc.) – we should do everything in our power to make it happen.

One strategy: when planning your course schedule at the beginning of the semester, throw in a scattering of buffer days – and as the semester progresses, sprinkle a few random (intentional) extensions in as your “surprise” stress-relievers. And on that note, here’s an example of what not to do.

Be wary of what and when you’re email-blasting. Be cognizant of what times you’re email-blasting information – especially sensitive/important information. Blasting exam grades at 9:30 PM on a Friday might not be a move…perhaps wait until Saturday morning for an email blast. Here are a few other tips related to email blasts:

- Ask for ACKs from at least one other TA before email-blasting something.

- Send out a consistent weekly announcement that contains assignments & due dates for the week.

- Try to keep email blasts to 1-2 a week.

- On that note, use targeted emails instead of email-blasting when possible (e.g. if a discussion attended by 30/1000 is canceled, it’s probably not worth pinging all 1000 students).

Kind words are important. In 161, we ask our proctors to run down a list of announcements at the start of an exam – and the very last announcement is always a set of kind words (e.g. “You’ll all do great!”). Similarly, we try to begin and end our email blasts with a few kind words as well, rather than going straight to business.

Try to build in support for one-on-one meetings with students. We have a few TA’s who dedicate a few of their hours towards these meetings each week - and they say every one of these meetings ends with the student saying something like “this has been so helpful, I was really stressed out before the meeting and now I am in such a good place and ready for…”. The difference between a private Piazza post or email and directly speaking to a struggling student is astounding. Discussions with & observations of these meetings in larger courses (e.g 61B, 61C) suggest that the effectiveness of these meetings require complementary extension-related course policy to scale as well (related: see these tips).

Piazza

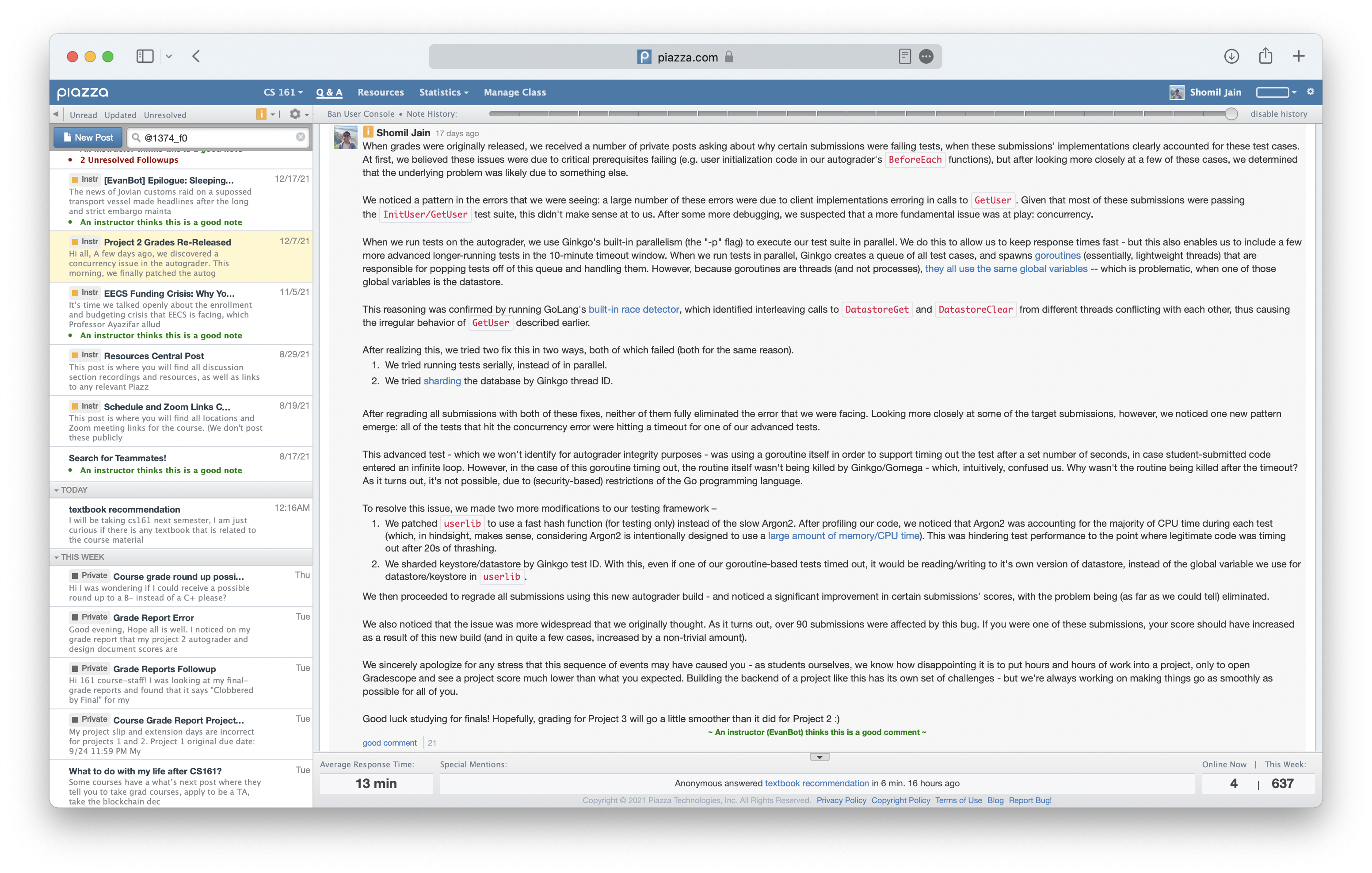

Give people updates on what’s happening on Piazza, instead of leaving posts unresolved for a long period of time. Try to make sure every single post & followup has a response. One thing that we use that I’d personally love to see in other classes: if you’re blocked on immediately resolving a post or don’t know what the answer is, then respond with a quick “Investigating” or “I’ve pinged XYZ to look into this” so students don’t think you’re ignoring posts. I think this might be especially relevant for megathreads & debugging-related posts that may go unresolved for a longer amount of time.

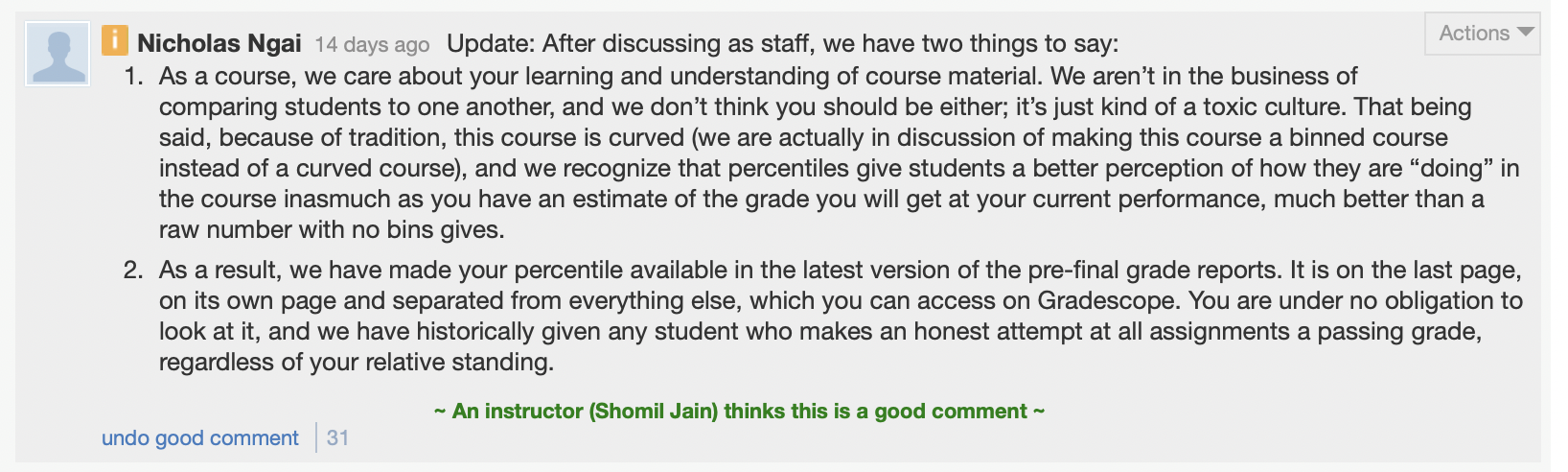

Instead of flat-out rejecting student demands, compromise wherever possible. Here’s an example: we release grade reports three times throughout the semester - after the midterm, before the final, and after the final. In our first round of grade reports, we received feedback (through our HW feedback channel) that percentiles were causing a stressful, competitive environment, where people were forced to compare themselves to their peers when looking at their grade reports. As such, we took these percentiles out in the second round. This immediately received pushback on Piazza – to which, we re-discussed and released this:

Be transparent. Earlier this semester, we released a buggy autograder, with some students receiving lower-than-intended scores. When we re-released grades a few days later, we posted this note along with our update.

Website

Have a centralized course website as a source of truth. Try to avoid scattering information across Piazza, Google Docs, emails, and a website - just put everything onto the website, and attach links to the websites from other sources. A clean web frontend is much, much better than a Piazza post or a Google Doc - and it’s certainly easier to find.

Put all important course links on your site’s homepage. This includes things like a standardized form to request extensions (here’s an example) and the office hours queue.

Please don’t conflate cheating with collaboration in your course syllabus. An earlier iteration of the CS 61C syllabus contained this note: We don’t want you sharing approaches, ideas, code or whiteboarding with other students.

At the time, it blew my mind that an introductory-level CS class at a top-tier university had an outright ban on whiteboarding with other students. Of course, this was in the context of academic integrity around course projects - but the specific wording that this particular policy used seemed (from my perspective as a student) cut-throat, competitive, and anti-collaborative.

I thought CS 184’s “Learning Cooperatively” section from the Spring 2021 syllabus was worded quite nicely: With the obvious exception of exams, we encourage you to discuss course activities with your friends and classmates as you are working on them. You will definitely learn more in this class if you work with others than if you do not. Ask questions, answer questions, and share ideas liberally.

And…again, the context here is a little different (e.g. upper-division vs. lower-division course), but my point here stands: emphasize collaboration in your syllabus, rather than denouncing it under the guise of “academic integrity”.

Exams

Always, always, always simplify student-facing logistics. When designing policies, procedures, and other student-facing documents, keep things simple - as simple as possible. The most critical example of this: exam logistics should never exceed one page. Here’s an example of what to do, and what not to do. Both of these examples are from Fall 2021.

During the early days of Zoom proctoring, proctoring policies sometimes exceeded ~12-17 pages (yes, this really happened). Creating excessive hoops for students to jump through distracts from actual course content – not to mention that we can achieve the same degree of effectiveness through a one-page policy.

Make the exam-taking experience as smooth as possible. Here are a few easy-to-catch things that we look for in our exams to make the experience better for our students:

- If you’re offering hybrid exams, pay close attention to equity across formats (e.g. limit short-answer questions to one sentence, so you’re not giving fast typers a significant advantage).

- When pre-testing, print out the exam. Sometimes, how pages line up influence the exam taking process (e.g. question on the front of a page, with the answer box on the back).

- Try to stay away from using big, convoluted blocks of text. Keep sentences short & concise to ensure the focus remains on course material.

Exams shouldn’t leave students feeling depressed. Follow Dan Garcia’s tips on writing good exam questions. A few major recommendations –

- Strive to make questions have a balance of A-level, B-level, and C-level questions.

- Every student should get some credit on each problem.

- Most problems should have a “fun” part that makes students think.

- Try very, very hard to keep exam means around 50-70%. Opening Gradescope to see a 30/100 is something that does impact a student’s mental health. I’ve been there - it really sucks to be in a position where you’re being told that you only “understood” 30% of a course, even if the overall class mean is low.

Allow students to discuss/ask questions about exam rubrics on Piazza, instead of taking a stance of “course staff knows best”. Here’s the message we post on Piazza: As always, it’s certainly possible that we may have made mistakes in grading. Please submit a regrade request if you spot an issue with how we applied the rubric to your submission, and feel free to leave questions (and any other exam-related feedback) in the follow-ups to this thread.

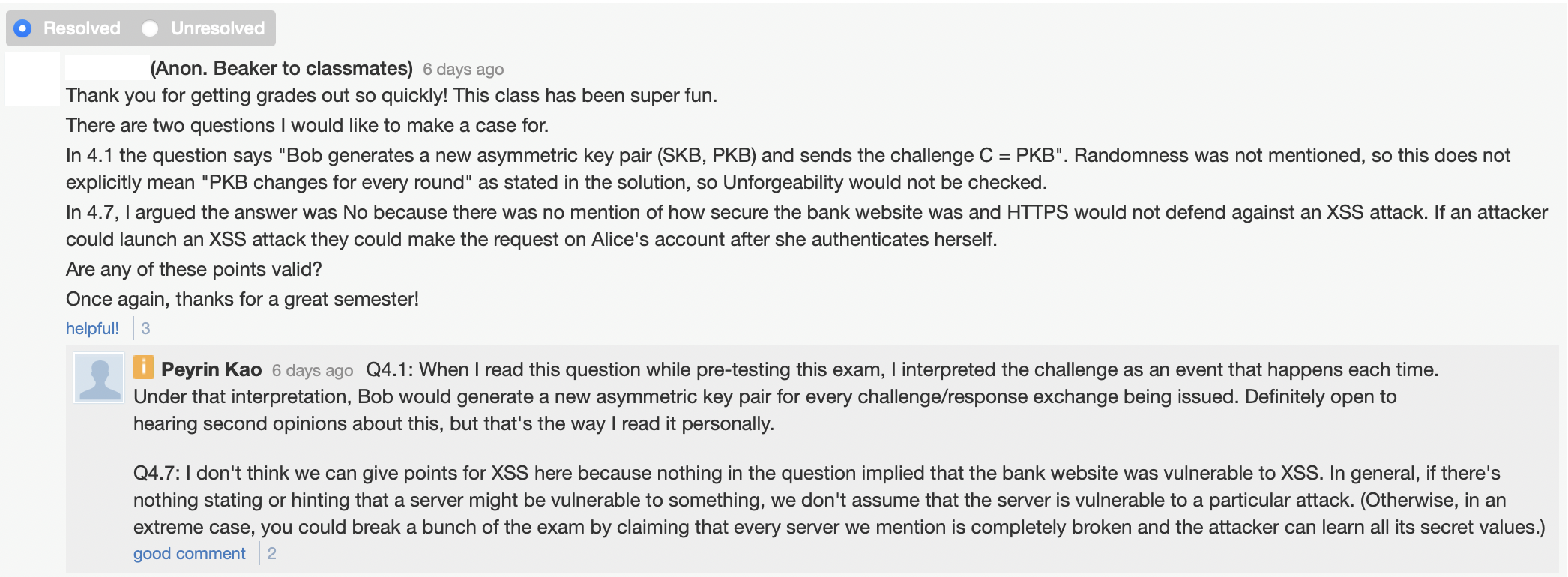

When discussing regrades, student-facing tone matters - a lot. Use neutral/positive phrases like “definitely open to hearing second opinions about this”, or “I don’t think we can give points for [X] here”, instead of negative/combative phrases. Regrade requests shouldn’t be an “us-vs-them” battle to the death; listen to students, try to hear their perspective, and share your own perspective until you’re able to reach a satisfactory conclusion.

Add a course bot! A few of our TA’s have been developing EvanBot (along with a pretty integrated course storyline) over the course of the past few semesters. Here are a few of Bot’s capabilities: making sensitive remarks about grading, responding to logistics requests in humorous ways, and sliding in a sly comment or two.

Internal

If you’re a head TA, these are a few things that have worked well on 161 staff.

Emphasize transparency. We’ve seen significant value from discussing admin-level logistics with our entire staff (e.g. much of our proctoring policy was crafted in a staff meeting a few semesters ago, and our 8-hour TA’s frequently contribute to decisions regarding course policy/workload and exam design). Creating barriers & hierarchy among staff degrades staff cohesion, reduces operational efficiency, and just doesn’t work well. We’re not Apple - we’re a bunch of (under)graduate student instructors just trying to teach our peers.

Keep roles flexible. If someone turns out to be really good at something, then let them work on that - even if it isn’t their official role. And, of course, reallocate other staff hours towards reducing their pre-assigned burden, if they’ve found something that they’re able to do really really well.

Keep hours flexible for office-hours “on-call” requests. This is super important during project weeks - if the queue is long, whoever’s assigned to a particular slot should ping Slack with a @here requesting assistance. Set an expectation for TA’s to dedicate a few staff hours towards being “on-call” during crunch weeks, and doubling up or stacking busy office hour times.